Making Science Pay With the SBIR

Making Science Pay With the SBIR

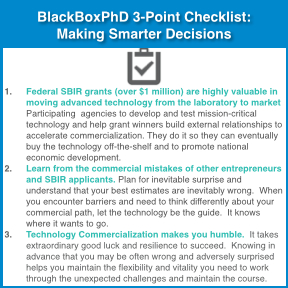

Finding funding support is a constant struggle for a lot of people, but especially for entrepreneurs and researchers. If you’re entrepreneur AND developing technologies based on science, you’re in luck. There’s a large pool of government funding put aside for something called Small Business Institutional Research (SBIR) grants. These are grants that are designed to give entrepreneurs upwards of $1 million to commercialize their research. The best part is that the government takes no equity from this support. It’s all done to advance disruptive technology and promote economic growth. But how do you compete successfully for these grants, and how do you commercialize scientific research? A few government agencies have contracted with intermediaries for advisors to help SBIR awardees develop their commercialization plan. James Brown is one of these advisors. I met him because he’s a fellow Stanford alum and runs the Innovation SoCal, a group in Los Angeles accelerating the economic and social value of new science and technology. In this week’s interview, he’ll talk about SBIR grants and some lessons for commercializing scientific research.

Jim, please tell us about your background and current work helping to commercialize research

I’ve been in the strategy and marketing field for advanced technology companies for most of my career. I started with BSEE from Stanford and an MS (MBA) from the MIT Sloan School. At that time I was interested in applying the mathematics of electrical engineering to the analysis of economic and social problems. After two years in the military, I spent several years as a defense policy analyst using game theory to simulate tactical combat and evaluate weapon systems effectiveness. Interested in applying similar analytics in business, I turned to corporate strategic planning and worked for several large corporations in the information technology industry. This led me to set off on my own to provide independent analytical planning and market research to large information technology companies.

I had always had a strong interest in advanced technology ventures and began to mix new venture projects with my large company services. That led to an amazing 4-year experience with Teradata Corporation, where I served on the company’s executive committee as it grew from $3 million to over $300 million in sales on its way to annual sales over $3 billion today. That sealed my fate, and I have now focused on all of my research and advisory work on emerging advanced technology companies. This has led to my involvement Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grants, a multi-agency federal program providing upwards of $1.5 million to move new and disruptive technologies from research laboratories to commercial markets.

What are government organizations looking for when they give SBIR funding? More than their overall purpose to stimulate small businesses, what specific qualities are they looking for in applicants and what outcomes would they like to see accomplished?

Each participating government agency establishes its own objectives and criteria for awarding SBIR grants — all within the common framework of the program’s enabling legislation. For the National Science Foundation, with which I am most familiar, the objective is to advance new and disruptive technology to the point of commercial viability where commercial revenues can sustain further advance the technology.

For the Defense Department and other agencies, the objectives are somewhat different. These agencies use the SBIR program to advance technologies vital to their mission. If the technologies become viable, these agencies are ofte

n the first buyers of products or services based on the technology. Nonetheless, these agencies require that the funded companies develop sustainable non-government revenue so that the agencies can purchase the technology or associated products off-the-shelf.

You also asked about the applicants. In my experience, about 70 percent of SBIR grants go to former university researchers who developed the novel technology as part of the Ph.D research and continued work at the university for several years thereafter. At some point, they form a company, obtain a  license to the technology from their university and apply for a SBIR grant. Interestingly, in my experience almost 70 percent of these folks are immigrant citizens who came to the US for their advanced education.

license to the technology from their university and apply for a SBIR grant. Interestingly, in my experience almost 70 percent of these folks are immigrant citizens who came to the US for their advanced education.

What are some success stories that you’ve have seen in commercializing research, either with your own work or others?

The SBIR is a two-phase grant program. The Phase I grant of upwards of $100 thousand is a 9 to 12 month program to test the concept feasibility. The Phase II grant of upwards of $1 million is an 18 to 24 month program to develop and test product prototypes. My work is primarily with those who have received Phase I grants and have to develop a viable commercialization plan to win the Phase II grant.

Along the way, companies with SBIR grants often raise money and establish early customer and supplier relationships. I worked with SBIR grant winners who have received $3 million to $6 million in venture capital investment while on their Phase I and Phase II grants. I am working now with a company that received $5 million in outside investment and used some of that money to public via a reverse merger with a corporate shell. I am personally aware of the success of Cree Inc., a manufacturer of LED lighting products with over $1 billion in annual sales, which was started on SBIR grants in the late 1980s. Associates tell me that Broadcom, was started on SBIR grants.

What are the main mistakes that researchers make who want to commercialize their own research? What are the main mistakes that entrepreneurs/business people make when they seek to identify a researcher and commercialize that person’s research (i.e., license a technology and market it)?

For both parties one main mistake is misunderstanding of how much time and money it will take to achieve sustainable operations. Both overestimate revenues, under estimate costs and slip critical commercialization milestones. But your question suggests a sharper distinction between researchers and entrepreneurs than I see in successful early stage, advanced technology companies.

For these companies, commercialization is really an organic extension of the research process. Scientific research moves into engineering and product development. Prototype products move into early testing and evaluation with interested companies. Interested companies become customers and reference accounts for future sales. Because the technology is new and usually focused on solutions to critical and demanding problems, the commercialization process is sustained by engineer to engineer problem-solving conversations. The process is less one of a researcher finding an entrepreneur or entrepreneur finding a researcher. Often the researcher is the entrepreneur or the scientist and entrepreneur already know each other well before the emergence of a commercialization or new venture opportunity. Shortcutting or disrupting this organic process almost always causes problems. It is almost as if the technology knows where it wants to go, and the scientists, engineers, investors and entrepreneurs work in its support.

What qualities or characteristics do you think separate successfully commercialized research from unsuccessful attempts to commercialize research? These could be differences in the team, the environment, or the product itself.

What qualities or characteristics do you think separate successfully commercialized research from unsuccessful attempts to commercialize research? These could be differences in the team, the environment, or the product itself.

In a sense, what separates success and failure in commercialization is an incredible amount of luck and resilience. So many things have to happen right for commercial success. From this perspective, the successful commercialization efforts rightly anticipate the future and have the will and means to recover from surprise. Beyond that, any of your mentioned items can break a commercialization process. The team may fracture, the technology or product may not work, the targeted problem may resolve in other ways, or competitors may unexpectedly produce a better solution. And even if all that is right, there may be no economically viable path into a market. Good problem-solving along the way may mitigate these things. But in many cases, time may prove that commercialization is not possible.

Any other comments or thoughts on how people (e.g., entrepreneurs, researchers, or business people) can apply your work to improve their daily lives or work?

My work with emerging advanced technology ventures has given me enormous respect for the technology commercialization effort. Nothing, it seems, can completely prepare you for the experience. Sure, there are right ways and wrong ways and better ways and worse ways. But in the end, each commercialization process is unique. As such, the critical knowledge and methods necessary for success must rise from the process itself. If there is anything my work offers for improving the daily lives of those involved in the process, it is to approach the process with a degree of humility. You will be challenged and brought to your knees by unanticipated developments. You will fail, recover, and fail again whether the effort is successful or not. You will need to work with others and learn to meld your experience and perspective with theirs. And above, I think, you need to respect the technology and let it find its way. With that humility and respect, I think you can approach the process with an ease and vitality that can sustain you. As with all great adventures, you will learn much from effort, and you will be changed.

James L. Brown is a strategic advisor to emerging, advanced technology companies. He works with scientists, engineers, entrepreneurs and investors to accelerate the commercialization of advanced technology. He also works as an executive counselor helping them frame the issues they face in moving their business forward and in harnessing the spirit and vitality of their teams for effective and rewarding work. For more information, his LinkedIn profile.

Pingback: pengumuman cpns 2017

Pingback: 5 star resort in dominican republic

Pingback: Event Management Company in Hyderabad

Pingback: how to make money with a iphone

Pingback: Hyderabad Corporate Event Planning

Pingback: AME

Pingback: Boliden

Pingback: must watch

Pingback: barn architecture styles

Pingback: حاصل على شهادات عالمية من الويبوماتركس

Pingback: pertamina persero

Pingback: العراق

Pingback: empresa informatica

Pingback: lowongan kerja terbaru

Pingback: gvk bio recent news

Pingback: guaranteedppc.com

Pingback: 卷筒纸

Pingback: Premature Ejaculation

Pingback: in vitro DMPK assay development

Pingback: Elizabeth Bay Locksmith

Pingback: primodex

Pingback: sciences

Pingback: Tuzilac

Pingback: 토토사이트 추천

Pingback: bitcoincasino today

Pingback: bitcoin betting

Pingback: http://bitcoinsportsbook.info

Pingback: New Bitcoin Casino Welcome Bonuses & Free Spins

Pingback: click

Pingback: smettere di fumare

Pingback: for more

Pingback: Best online casino reviews in New Zealand

Pingback: UK Chat

Pingback: Discover

Pingback: fmovies.cab

Pingback: Walls Online Marketing is where you can get honest product and software reviews also great online marketing tips.

Pingback: Teen Chat Rooms

Pingback: HappierCitizens

Pingback: Olivia

Pingback: bmw maintenance Greensboro

Pingback: Foot Health

Pingback: bitcoin hosting

Pingback: 2019

Pingback: cleantalkorg2.ru

Pingback: #macron #Lassalle

Pingback: a2019-2020

Pingback: facebook

Pingback: facebook1

Pingback: javsearch.mobi

Pingback: website

Pingback: best canadian pharmacy

Pingback: shop pharmacie

Pingback: amoxicillin pharmacy price

Pingback: personal loans for bad credit

Pingback: online canadian pharmacy

Pingback: Amoxil

Pingback: online pharmacies in canada

Pingback: generic zithromax india

Pingback: best ed drugs

Pingback: online pharmacy canada

Pingback: canadian online pharmacies

Pingback: antibiotic resistant seagulls

Pingback: allegra medication

Pingback: zyrtec 5mg chewable

Pingback: drugs without prescription

Pingback: zithromax z-pak price without insurance

Pingback: amoxicillin capsules 250mg

Pingback: ed pills without doctor prescription

Pingback: buy sildenafil

Pingback: best drug for ed

Pingback: erectile dysfunction medicines

Pingback: meyeynkf

Pingback: best ed pills

Pingback: where can i get azithromycin without a prescription

Pingback: buy furosemide online

Pingback: erythromycin price

Pingback: minocycline tablets

Pingback: buy ciplox

Pingback: buy prescription drugs online without

Pingback: augmentin 625 price india

Pingback: drug furosemide 20 mg

Pingback: buy zithromax online

Pingback: stromectol buy

Pingback: proventil for sale

Pingback: zithromax 500 mg

Pingback: synthroid hot flashes

Pingback: cheap ed pills from india

Pingback: azithromycin zithromax

Pingback: neurontin 204

Pingback: zithromax drug

Pingback: propecia and finasteride

Pingback: meds from india

Pingback: neurontin nursing implications

Pingback: india pharmacy mail order

Pingback: glyburide metformin

Pingback: stopping plaquenil abruptly

Pingback: mail order erectile dysfunction pills

Pingback: antibiotic amoxicillin

Pingback: metformin canada online

Pingback: finasteride no prescription

Pingback: propecia proscar

Pingback: generic ed pills

Pingback: erectile dysfunction medicines

Pingback: canadian pharmacies compare

Pingback: legit pharmacy websites

Pingback: roaccutane isotretinoin buy

Pingback: lisinopril 40 mg cost

Pingback: causes for ed

Pingback: ed treatment review

Pingback: cheap drugs online

Pingback: ed treatment drugs

Pingback: best ed pill

Pingback: stromectol for sale

Pingback: plaquenil generic cost

Pingback: plaquenil 200

Pingback: where to buy ivermectin pills

Pingback: stromectol medicine

Pingback: amoxicillin without a doctor's prescription

Pingback: best online drugstore

Pingback: best cure for ed

Pingback: zithromax 250 mg tablet price

Pingback: how to get zithromax over the counter

Pingback: stromectol pill

Pingback: generic ed pills

Pingback: plaquenil 5 mg

Pingback: cost of prednisone 40 mg

Pingback: order diet pills from canada

Pingback: weight loss pills from canada

Pingback: ivermectin brand

Pingback: online drugstore

Pingback: ivermectin pill cost

Pingback: buy ivermectin for humans uk

Pingback: best over the counter ed pills

Pingback: tamoxifen adverse effects

Pingback: tamoxifen rash pictures

Pingback: prednisone pill prices

Pingback: purchase prednisone no prescription

Pingback: order prednisone online canada

Pingback: cost of ivermectin

Pingback: best canadian online pharmacy

Pingback: the canadian drugstore

Pingback: buy prednisone mexico

Pingback: buy prednisone online india

Pingback: prednisone oral

Pingback: stromectol pill

Pingback: lasix cheap online

Pingback: neurontin capsules

Pingback: quineprox 80 mg

Pingback: prednisone 5084

Pingback: priligy mexico

Pingback: provigil medicine

Pingback: generic stromectol

Pingback: albuterol rx coupon

Pingback: zithromax 500mg

Pingback: buy lasix cheap

Pingback: gabapentin pharmacy

Pingback: plaquenil 400

Pingback: priligy price nz

Pingback: buy provigil reddit

Pingback: azithromycin purchase

Pingback: generic pills

Pingback: cheap generic ed pills

Pingback: cheap generic drugs from india

Pingback: plaquenil 200 cost

Pingback: buy plaquenil

Pingback: ivermectin 200mg

Pingback: buy plaquenil 10mg

Pingback: ivermectin 3mg tablets

Pingback: generic ivermectin

Pingback: order stromectol

Pingback: stromectol south africa

Pingback: compare ed drugs

Pingback: the best ed pills

Pingback: stromectol without prescription

Pingback: stromectol canada

Pingback: buy stromectol online uk

Pingback: prescription cost comparison

Pingback: Diflucan

Pingback: best online international pharmacies

Pingback: latisse brows

Pingback: nolvadex sale

Pingback: Thorazine

Pingback: Augmentin

Pingback: stromectol cvs

Pingback: stromectol 6 mg dosage

Pingback: where to get zithromax

Pingback: canadian drug pharmacy

Pingback: pain meds online without doctor prescription

Pingback: buy molnupiravir online

Pingback: п»їorder stromectol online

Pingback: ivermectin price usa

Pingback: Vuoi un pene più spesso?

Pingback: reduslim prezzo

Pingback: reduslim prezzo

Pingback: reduslim prezzo

Pingback: reduslim controindicazioni

Pingback: reduslim farmacia

Pingback: reduslim farmacia

Pingback: reduslim controindicazioni

Pingback: reduslim prezzo in farmacia

Pingback: Reduslim opiniones reales

Pingback: Reduslim Precio en la farmacia

Pingback: Reduslim precio Comprar en farmacias españolas (original, sitio oficial)

Pingback: Reduslim precio en farmacias españolas original, sitio oficial

Pingback: Reduslim precio Comprar farmacias original, sitio oficial

Pingback: Reduslim precio Comprar linea en farmacias españolas original, sitio oficial

Pingback: Mejores precios en España Comprar linea (original, sitio oficial)

Pingback: Miglior prezzo Italia Comprare online (originale, sito ufficiale)

Pingback: Miglior prezzo Italia Comprare online (originale, sito ufficiale)

Pingback: How to buy a prescription drug without a prescription?

Pingback: How to buy a prescription drug without a prescription?

Pingback: How to buy a prescription drug without a prescription?

Pingback: How to buy a prescription drug without a prescription?

Pingback: How to buy a prescription drug without a prescription?

Pingback: How to buy a prescription drug without a prescription?

Pingback: How to buy a prescription drug without a prescription?

Pingback: How to buy a prescription drug without a prescription?

Pingback: How to buy a prescription drug without a prescription?

Pingback: How to buy a prescription drug without a prescription?

Pingback: How to buy a prescription drug without a prescription?

Pingback: Where will they sell pills without a prescription with delivery?

Pingback: Where do you sell pills without a prescription with delivery?

Pingback: Where can I go to buy pills without a prescription?

Pingback: Coupons for the purchase of drugs without a prescription

Pingback: Promo code for the purchase of drugs, you can buy without a prescription

Pingback: Sale of drugs, you can buy without a prescription

Pingback: Buy Atarax online

Pingback: Get Atarax 10 mg, 25 mg cheap online

Pingback: Safe to Buy Atarax Without a Prescription

Pingback: Safe to Buy Atarax Without a Prescription

Pingback: Cheap buy Atarax online

Pingback: Safe to Buy Atarax Without a Prescription

Pingback: Get Atarax 10 mg, 25 mg cheap online

Pingback: Get Atarax 10 mg, 25 mg cheap online

Pingback: Buy Atarax 10 mg, 25 mg online

Pingback: Buy Atarax 10 mg, 25 mg online

Pingback: Buy Atarax 10 mg, 25 mg online

Pingback: Buy Atarax 10 mg, 25 mg online

Pingback: Buy Atarax 10 mg, 25 mg online

Pingback: Atarax drug for mental health buy online or pharmacy

Pingback: Atarax drug for mental health buy online or pharmacy

Pingback: Atarax drug for mental health buy online or pharmacy

Pingback: Atarax drug for mental health buy online or pharmacy

Pingback: online pharmacy australia

Pingback: indian trail pharmacy

Pingback: purchase cipro

Pingback: ed pills that really work

Pingback: sleeping pills over the counter

Pingback: zithromax 500

Pingback: stromectol 3 mg tablet

Pingback: can i order generic avodart without rx

Pingback: buy erection pills

Pingback: prescription without a doctor's prescription

Pingback: buying propecia no prescription

Pingback: canadian pharmacy no rx needed

Pingback: ciprofloxacin 500 mg tablet price

Pingback: buy cipro online canada

Pingback: ed treatment drugs

Pingback: best ed pills non prescription

Pingback: how can i get generic propecia without insurance

Pingback: buy birth control over the counter

Pingback: birth control pills without seeing a doctor

Pingback: ed drugs

Pingback: treatment for ed

Pingback: 54 prednisone

Pingback: canadian online pharmacy

Pingback: best european online pharmacy

Pingback: online shopping pharmacy india

Pingback: Paxlovid buy online

Pingback: Paxlovid over the counter

Pingback: amoxicillin 875 mg tablet

Pingback: legitimate canadian pharmacy

Pingback: best rated canadian pharmacy

Pingback: herbal ed treatment

Pingback: order cytotec online

Pingback: cytotec abortion pill

Pingback: cheap kamagra

Pingback: ivermectin cost uk

Pingback: ivermectin cream uk