Hey Elliot, can you tell us about your background and current research?

I’m trained as a social psychologist, which means that I think a lot about how other people and our thoughts and feelings affect our behavior. I also use neuroimaging tools such as functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI, to learn more about how our brains support social psychological processes. My current research is about health behavior change, and explores various ways that people can be successful in health goals such as smoking cessation and dieting.

One of the reason’s I think people are so excited about research like yours on the brain and behavior is that the brain is a black box — it’s this mysterious part of our bodies that we can’t see but affects pretty much everything we do. In such short time, neuroscience research has come a long way in learning about people’s brains and how they affect behavior. Do you think we’ll reach a day when people will be able to control their brains the way we control our arms or legs? For example, if we want to stop eating cookies, will we be able to know how to activate an area in our brains that will make us stop wanting to eat the rest of the box?

I think all of the same things you said about the brain (that it’s a black box, it’s mysterious, and it’s powerful) are  equally true of the mind. Have we reached a point in psychology–let alone in neuroscience–where we know how to think about cookies so we can make ourselves stop wanting them? Not yet. My research uses neuroimaging as a way of helping us answer those kinds of psychological questions. For example, does knowing what happens in our brains when we try to resist the urge to eat a cookie help us improve our abilities in cookie-control?

equally true of the mind. Have we reached a point in psychology–let alone in neuroscience–where we know how to think about cookies so we can make ourselves stop wanting them? Not yet. My research uses neuroimaging as a way of helping us answer those kinds of psychological questions. For example, does knowing what happens in our brains when we try to resist the urge to eat a cookie help us improve our abilities in cookie-control?

Neuroscience is a useful tool for research on self-control because our intuitions about how self-control works aren’t always right. Getting another measure of self-control beyond what people say about it can provide insights that wouldn’t be possible with other measures alone. For example, self-control feels hard, and lapses of self-control feel easy, leading to the belief that it takes more energy to exert control than it does to give in to a temptation. But, at a neurophysiological level, it turns out that’s not true. Your brain doesn’t work any harder when you’re trying to resist the urge to indulge than when you’re actually eating that cookie. This, in turn, opens up some interesting new questions: why does self-control feel hard even though it’s not energetically costly? Is our sensation of effort, rather than actual effort required, the real barrier to succeeding at self-control?

The current state of neuroscience research seems similar to me to the state of genetics/genomics in that there’s a lot of promise and expectations for the field but also a lot of confusion about what we can get out of it now and what we can realistically expect in the future. When we interviewed Eleazar Eskin, a computer science and genetics researcher, he cleared up a lot of myths about what questions genetics research can answer currently and what we can expect in the future. Can you do the same for neuroscience research? In other words, is the field of social neuroscience in a very “researchy” stage where we’re still learning the basics of the brain and behavior, or are we already able to apply it to change and improve people’s daily lives and behaviors? What type of insights do you expect in the future from social neuroscience that could be applied to improve people’s lives?

That’s a very important question. It’s always critical for scientists to recognize the limitations of their tools and to have a sense of where their field is in its progression from observation and identification to understanding and useful application. That being said, I believe that the distinction between “basic” and “applied” research is a false dichotomy. There are plenty of ways that neuroscience research could be applied to improve people’s lives right now, while simultaneously answering so-called “basic science” questions. We have ongoing studies looking at the effects of self-control training protocols on neural function (called “brain training” in the popular press). These studies have illuminated the surprising ways that brain function changes with training, and also have suggested ways that we could tweak existing interventions to make them more effective.

There’s an idea of an “addictive personality” where people who are addicted to one thing are addicted to a lot of other things, and that it’s possible to cure addictions to everything simultaneously by getting rid of this addictive personality. I work in the center for behavioral and addiction medicine at UCLA but I still have trouble understanding this. Trained as a social psychologist, I’d guess that “addiction” is less of a personality trait that can be objectively measured and that it’s more something that affects almost everyone, but that self-regulation is affected by different things, depending on context, environment and other factors. Does research answer this question of whether this is an addictive personality?

There is a powerful current in the sea of addiction research that is flowing in this direction. The idea is that addiction reflects, in part, certain disruptions in the way the brain’s reward system operates. The logic is that, for whatever reason, some people’s reward systems are more prone to respond strongly to reward at first, then be under-responsive afterwards. This propensity is further complicated by the fact that certain drugs, notably cocaine and heroin, can further damage the reward system in ways that make it even harder to escape addiction, so there is a cycle of disruption to the reward system that is self-perpetuating. By this logic, it makes sense to think that someone addicted to certain drugs might be more likely to become addicted to other rewards as well.

Our Institute for Prediction Technology focuses on using data to predict events, like people’s behaviors. Much of your work is similar in that you’ve shown how we can look at what’s going on in people’s brains and use that information to predict their behavior. Can you elaborate on your work in this area and give an example of how neuroscience work can predict behavior? For example, you and I have a lot in common– we overlapped at Stanford and UCLA, we’re both Jews, we’re interested in psychology and behavior, and we both like Hal Hershfield and Danny Oppenheimer. Would there be anything in neuroscience research that could have predicted similarities between us that existed or will exist in the future, like certain preferences or behaviors?

To start, let me say that I am uncomfortable with the idea of going on the record as liking that scoundrel, Danny Oppenheimer. But aside from that, your question is very astute. Another way to put it is that there are plenty of non-neuroscience data points that could potentially be used to predict our behavior. I bet that Facebook, for example, knows about all of those similarities on some level and can accurately use it to predict that we’d both like Cendri Hutcherson and Nicole Giuliani, too. The challenge for neuroscience–and it is a significant challenge–is to prove its usefulness for predicting thoughts, feelings, attitudes, behaviors, and so forth above and beyond what could be predicted from other, far less costly methods. Neuroscience gains its advantage from its ability to measure psychological processes under the hood as they occur. People tend not to have great introspective access to those processes; all we can see is their output. For example, in my own work I’ve found that cigarette smokers don’t have any great insight into why they succeed or fail in a quit attempt. Or they may have “lay theories” about what prompts them to relapse, but those theories often turn out to be incorrect. That is one reason why looking at their brains helped me and my colleagues (including the incomparable Emily Falk) predict who would relapse and who wouldn’t with much greater accuracy that we would have been able to with only non-neuroimaging measures.

Our interview with Danny Oppenheimer got me stuck on thinking about cookies in examples so let’s stick with that. What are some reasons why some people have such a tough time controlling their cookie intake, while other people are really good at eating just 1 or 2 cookies? In other words, what are some common reasons why people fail to self-regulate and how can we overcome those issues?

This issue of self-control is at the heart of my research. I think about it every day and I still do not have a satisfying answer, so I’ll tell you where the research is right now and hope to have much more clarity as we continue to dig into this question. The classic answer is that the decision to eat the cookie or not hinges on the outcome of a battle between impulsive, “hot” forces and controlled, “cold” ones. The demon on one shoulder tells you to eat it and the angel on the other tells you not to. In this light, the answer to your question is that self-control fails because the cookie is simply too tempting or the strength of the ability to resist it is too weak or both.

outcome of a battle between impulsive, “hot” forces and controlled, “cold” ones. The demon on one shoulder tells you to eat it and the angel on the other tells you not to. In this light, the answer to your question is that self-control fails because the cookie is simply too tempting or the strength of the ability to resist it is too weak or both.

This is indeed how that decision feels. But the hot vs. cold story has some problems. The brain doesn’t nearly separate into “hot” versus “cold” regions. Sometimes people will engage very controlled thinking in order to have a “self-regulation” failure, such as when a dieter makes elaborate plans to savor a particularly delicious temptation. Sometimes people make a habit of self-control, such as when a distance runner gets up in the morning and “automatically” sets out on a job. Therefore, self-control is only sometimes, but by no means always, a battle between impulsive and controlled processes. Many other times it’s a matter of habit, planning or situational forces. In fact, I’d say that if you find yourself in a situation where you are sitting directly in front of the tempting cookie then you’ve already failed. It is unrealistic to expect yourself to be able to engage that (especially difficult) kind of self-control on a consistent basis. I find that this driving problem is a good analogy: how do you avoid running red lights? One bad strategy is to slam on the brakes when the light turns red. A better strategy is to gradually slow down when the light turns yellow. And the best strategy is to take the alternate road that has no stop light at all.

Do you have any final insights on how people can apply your research to their lives or work? For example, this can be general advice they can apply in daily life, ideas for creating technologies or products that can improve people’s lives, or ways your work can be applied to improve relationships?

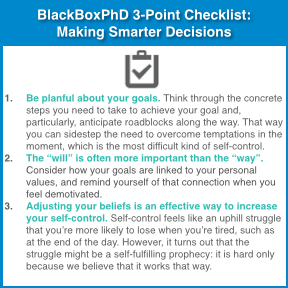

One prominent line of research in my lab right now emphasizes the limits of people’s abilities to control their impulses in the heat of the moment. Some people are definitely better than others at this, but overall that kind of immediate self-control should be a last-ditch strategy. I am a big fan of planning, or trying to anticipate situations that could lead to self-control failure and to avoid them in the first place. Peter Gollwitzer has generated decades worth of evidence that “implementation intentions”, or simple if-then plans to deal with stumbling blocks as they come up, promote self-regulation. Taking the time to think through the details of your plan and potential obstacles is well worth the time.

The other practical implication of our work is that the motivation to engage in self-control is often far more important than the actual ability to do so. Most people are physically capable of resisting the cookie. What they are lacking is the will to do it. In those moments, it can be helpful to consider why you want to resist the cookie rather than merely how. In particular, ask yourself why resisting the cookie aligns with your core values as a person and your long-term goals? There is a robust literature showing that these kinds of “self-affirmations” can help us achieve our goals in a variety of domains.

Pingback: cheap seo services india

Pingback: panselmas

Pingback: GVK Biosciences

Pingback: Event Management Company in Hyderabad

Pingback: juegos friv

Pingback: taruhan bola

Pingback: iraq Colarts

Pingback: Engineer SEO Aws ALKHAZRAJI

Pingback: ADME

Pingback: Klinik gigi jakarta utara

Pingback: lowongan kerja makassar september

Pingback: iraqi Seo

Pingback: AwsUoD Alkhazraji

Pingback: www.cpnsnews.com

Pingback: loker cpns daerah 2019

Pingback: serviços informática

Pingback: find a real estate agent

Pingback: GVK BIO New Deals

Pingback: Appliance repair North York

Pingback: what is forex trading

Pingback: 검증사이트

Pingback: Lamborghini Hoverboard

Pingback: how do I cure premature ejaculation

Pingback: Java Tutorial

Pingback: ephedrine steroid

Pingback: free forex signals

Pingback: payday advance

Pingback: astrology zone

Pingback: Ambika Ahuja Jaipur Escorts

Pingback: NEHA TYAGI MODEL JAIPUR ESCORTS

Pingback: JAIPUR ESCORTS ALIYA SINHA

Pingback: BANGALORE COMPANION ESCORTS

Pingback: Dhruvi Jaipur Escorts

Pingback: JAIPUR ESCORTS MODEL DRISHYA

Pingback: Heena Khan Bangalore Escorts

Pingback: Jiya Malik High Profile Jaipur Escorts Model

Pingback: FUN WITH JAIPUR ESCORTS PUJA KAUR

Pingback: XXX BANGALORE ESCORTS ROZLYN MODEL

Pingback: Enjoy With Jaipur Escorts Tanisha Walia

Pingback: Selly Arora Independent Bangalore Escorts

Pingback: RUBEENA RUSSIAN BANGALORE ESCORTS

Pingback: Bristy Roy Independent Bangalore Escorts

Pingback: SRUTHI PATHAK MODEL ESCORTS IN BANGALORE

Pingback: Bangalore Escorts Sneha Despandey

Pingback: Radhika Apte Model Escort in Bangalore

Pingback: Goa Escorts Eva J Law

Pingback: Kolkata Escorts Services Fiza Khan

Pingback: Banja Luka

Pingback: Ruby Sen Kolkata Independent Escorts Services

Pingback: Diana Diaz Goa Independent Escorts Services

Pingback: Diksha Arya Independent Escorts Services in Kolkata

Pingback: Devika Kakkar Goa Escorts Services

Pingback: Rebecca Desuza Goa Independent Escorts Services

Pingback: Yamini Mittal Independent Escorts Services in Goa

Pingback: Simmi Mittal Kolkata Escorts Services

Pingback: Kolkata Escorts Services Ragini Mehta

Pingback: Navya Sharma Independent Kolkata Escorts Services

Pingback: Elisha Roy Goa Independent Escorts Services

Pingback: Alisha Oberoi Independent Escorts in Kolkata

Pingback: Divya Arora Goa Independent Escorts Services

Pingback: Simran Batra Independent Escorts in Kolkata

Pingback: Ashna Ahuja Escorts Services in Kolkata

Pingback: Sofia Desai Escorts Services in Goa

Pingback: Goa Escorts Services Drishti Goyal

Pingback: Mayra Khan Escorts Services in Kolkata

Pingback: Sruthi Pathak Escorts in Bangalore

Pingback: Ambika Ahuja Jaipur Escorts Services

Pingback: sirius latest movs181

Pingback: comment763

Pingback: comment420

Pingback: comment513

Pingback: comment610

Pingback: comment340

Pingback: comment246

Pingback: comment831

Pingback: comment467

Pingback: comment814

Pingback: comment594

Pingback: comment67

Pingback: comment765

Pingback: comment941

Pingback: comment638

Pingback: comment746

Pingback: comment613

Pingback: comment380

Pingback: comment725

Pingback: comment298

Pingback: comment586

Pingback: comment468

Pingback: comment130

Pingback: comment75

Pingback: comment342

Pingback: comment320

Pingback: comment109

Pingback: comment879

Pingback: comment914

Pingback: comment944

Pingback: comment608

Pingback: comment912

Pingback: comment285

Pingback: comment369

Pingback: comment59

Pingback: comment536

Pingback: comment791

Pingback: comment193

Pingback: comment578

Pingback: comment462

Pingback: comment253

Pingback: comment372

Pingback: comment274

Pingback: comment31

Pingback: Sruthi Pathak Bangalore Female Escorts

Pingback: latestvideo sirius416 abdu23na6053 abdu23na73

Pingback: new siriustube879 abdu23na8483 abdu23na11

Pingback: tubepla.net download739 afeu23na8248 abdu23na69

Pingback: tubepla.net download757 afeu23na3012 abdu23na38

Pingback: Sruthi Pathak Bangalore Escorts Services

Pingback: Trully Independent Bangalore Escorts Services

Pingback: Fiza Khan Kolkata Independent Call Girls Services

Pingback: Ruchika Roy Kolkata Escorts Call Girls Services

Pingback: Fiza Khan Kolkata Independent Escorts Call Girls Services

Pingback: Fiza Khan Kolkata Call Girls Escorts Services

Pingback: Diksha Arya Kolkata Escorts Call Girls Services

Pingback: Diksha Arya Kolkata Independent Escorts Call Girls Services

Pingback: 안전놀이터

Pingback: Nidika Offer Call Girls in Bangalore

Pingback: Hyderabad Escorts Call Girls Services

Pingback: Pune Escorts Services Call Girls

Pingback: Bangalore Cheap Escorts Sevices

Pingback: pain meds without written prescription

Pingback: Goa Escorts Call Girls

Pingback: prescription drugs canada buy online

Pingback: discount prescription drugs

Pingback: propecia

Pingback: cbd oil for sale locally

Pingback: best cbd oil

Pingback: cbd oil benefits

Pingback: online prescription for ed meds

Pingback: sildenafil injection

Pingback: lbgoeggt

Pingback: how long does it take for zithromax to work

Pingback: buy amoxicillin 250mg

Pingback: generic lasix for sale

Pingback: buy azithromycin 1000mg

Pingback: ivermectin coronavirus

Pingback: combivent medication

Pingback: diflucan and monistat

Pingback: synthroid 137

Pingback: hims propecia

Pingback: neurontin milligrams

Pingback: metformin for prediabetes

Pingback: plaquenil and lupus

Pingback: monthly cost of without insurance

Pingback: amoxil 250

Pingback: brand gabapentin

Pingback: quineprox 10 mg

Pingback: 5mg prednisone

Pingback: priligy tablets

Pingback: ivermectin 6 tablet

Pingback: ventolin price canada

Pingback: azithromycin 250 mg

Pingback: buy plaquenil 10mg

Pingback: order prednisone

Pingback: stromectol pill

Pingback: zithromax 500mg tab

Pingback: 2mg tizanidine

Pingback: nolvadex pill

Pingback: lilly baricitinib